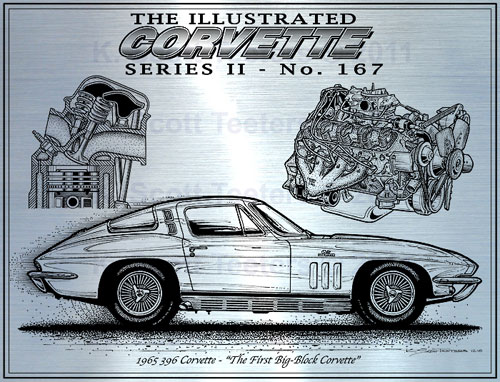

The Latest Installment in VETTE Magazine’s “Illustrated Corvette Series” by K. Scott Teeters

Were it not for NASCAR Chevys trailing behind nearly everyone in the early ’60s, there may never have been a big-block Corvette. Fuelie Corvettes were doing very sell in SCCA sports car racing, but the NASCAR Chevys where in trouble. While GM was officially not racing in the late ’50s and early ’60s, Duntov and a few other Chevy engineers kept select Chevy racers supplied heavy-duty specialty parts for field testing. Engineers tried to help with the Z11 Impala option that made a 427 out of the 409 truck motor. The car performed well as a drag racer, but wasn’t a competitive stock car racer.

In the Summer of ’62, Chevy engineer Dick Keinath was tasked to design the next generation big-block Chevy engine. Since the 348/409 was called the Mark I, the new engine was named, Mark II. The new block was based on the thick bottom end design of the 348/409 for low end strength, and new free-breathing heads.

Over in the Corvette camp, Duntov was making jaws drop at the GM test track with his CERV I and in June got approval from Chevy general manager, Bunkie Knudsen for the CERV II. A few days later, GM’s president, Frederick Donner ordered the project stopped. Days later, Knudsen approving Duntov’s Grand Sport proposal. By the end of the year, Donner had had it! On January 21, 1963, lightning bolts fell from upon high. “Thou shall not race GM cars!” Thus ended Chevrolet’s direct involvement with the racing.

Meanwhile, the Mark II was ready for some NASCAR field testing, so Smokey Yunick, the perfect back-door privateer racer, was called upon. With Johnny Rutherford at the wheel of Yunick’s 427 ’63 Impala, the car set the fastest speed of the month and a world’s record for a closed-course at a then-blistering 165.183-MPH! Yunick guestimated that the Mark II was pulling at least 500-HP and everyone could tell that was no ordinary Chevy and Also, Duntov loaned a Mark II prototype to Micket Thompson to install into a ;63 Z06 for some road racing field testing. The legend of the “Chevy Mystery Motor” was born

Aware of the GM ban on racing, the press was left to speculate the fate of the Mystery Motor. The following March at a press conference, Donner was asked about that fast Chevy that was raced at Daytona the month before. Donner replied that he didn’t know anything about it. Seriously embarrassed, Donner was determined to forbid GM’s direct involvement in racing.

But all was not lost. In early ’64 Zora Duntov was charged to form a team of engineers to make the Mark II into a production engine. Duntov and his Corvette team had worked very hard with the new Sting Ray to achieve a 50/50 weight balance, so adding front end weight was against his design sense. But the team got seriously motivated when it was learned that Carroll Shelby was putting the big 427 Ford NASCAR engine into his Cobras.

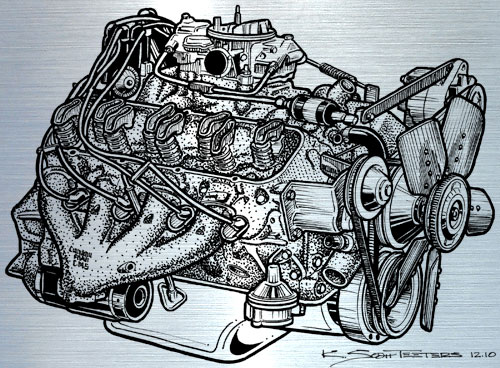

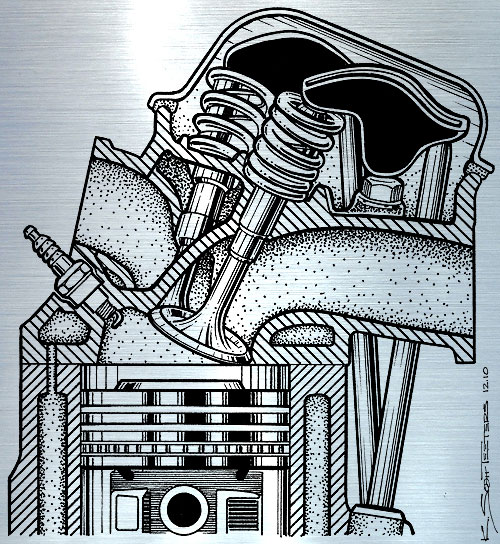

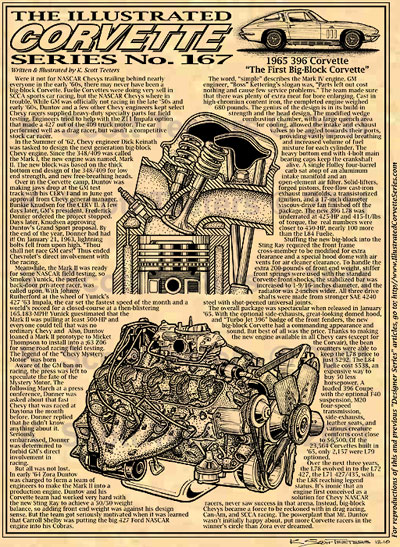

The word, “simple” describes the Mark IV engine. GM engineer, “Boss” Kettering’s slogan was, “Parts left out cost nothing and cause few service problems.” The team made sure that there was plenty of extra meat for bore enlarging. Cast in high-chromiun content iron, the completed engine weighed 680-pounds. The genius of the design is in its build-in strength and the head design. The modified wedge combustion chamber, with a large quench area for cooling, allowed the intake and exhaust valves to be angled towards their ports, providing vastly improved breathing and increased volume of fuel mixture for each cylinder. The heavy bottom end with 4-bolt main bearing caps keep the crankshaft alive. A single Holley four-barrel carb sat atop of an aluminum intake manifold and an open-element air filter. Solid-lifters, forged pistons, free-flow cast-iron exhaust manifolds, a transistorized ignition, and a 17-inch diameter viscous-drive fan finished off the package. The new 396 L78 was underrated at 425-HP and 415-ft/lbs of torque, the real numbers were closer to 450-HP, nearly 100 more than the L84 Fuelie.

Stuffing the new big-block into the Sting Ray required the front frame cross-member to be modified for extra clearance and a special hood dome with air vents for air cleaner clearance. To handle the extra 200-pounds of front end weight, stiffer front springs were used with the standard Corvette front shocks, the stabilized bar was increased to 1-9/16-inches diameter, and the radiator was 2-inches wider. All three drive shafts were made from stronger SAE 4240 steel with shot-peened universal joints.

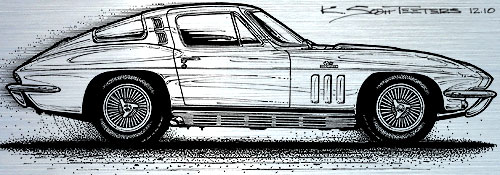

The overall package was spectacular when released in January ’65. With the optional side-exhausts, great-looking domed hood, and “Turbo Jet 396” badge of the front fenders, the new big-block Corvette had a commanding appearance and sound. But best of all was the price. Thanks to making the new engine available in all Chevy cars (except for the Corvair), the bean counters were able to keep the L78 price to just $292. The L84 Fuelie cost $538, an expensive way to buy 50 less horsepower. A loaded 396 Coupe with the optional F40 suspension, M20 four-speed transmission, side-exhausts, leather seats, and various creature comforts cost close to $6,500. Of the 23,564 Corvettes built in ’65, only 2,157 were L79 optioned.

Over the next three years, the L78 evolved in to the L72 427, the L71 427/435, with the L88 reaching legend status. It’s ironic that an engine first conceived as a solution for Chevy NASCAR racers, never saw success in that arena. Instead, big-block Chevys became a force to be reckoned with in drag racing, Can-Am, and SCCA racing. The powerplant that Mr. Duntov wasn’t initially happy about, put more Corvette racers in the winner’s circle than Zora ever dreamed.

Scott

Parchment paper and Laser-Etched prints are available HERE.