by Scott Teeters as written for Vette magazine and republished from Super Chevy

Trend Setting – Part 11: A look back at Chevrolet’s experimental, prototype, concept car, and show car Corvettes.

Dateline November 2015: In the last installment of our series we told you about the 1970 XP-882 mid-engine, transverse Corvette prototype. Chevrolet landed a KO punch on Ford and AMC, never knowing what hit them. So why didn’t Chevrolet strike while the iron was hot? Perhaps because the XP-882 didn’t generate the sizzle from the crowd the way the Mako Shark II did when it made its debut in 1965, Chevrolet took the XP-882 home and did little with it for over a year.

The drivetrain was engineered to take a big-block 454 and a four-speed transmission was designed into the unique Toronado-based transfer case. To accommodate the rear weight bias, wider tiers were fitted onto the car. But there were two overriding factors at work. First, the production Corvette was selling well enough and they’d spent a fortune transforming the car into the Mako Shark style. And second, on November 10, 1970, GM acquired the license rights to develop the Wankel engine, which proved to be a huge distraction.

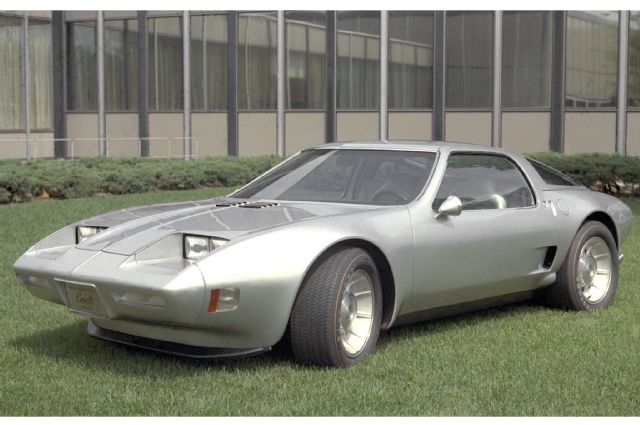

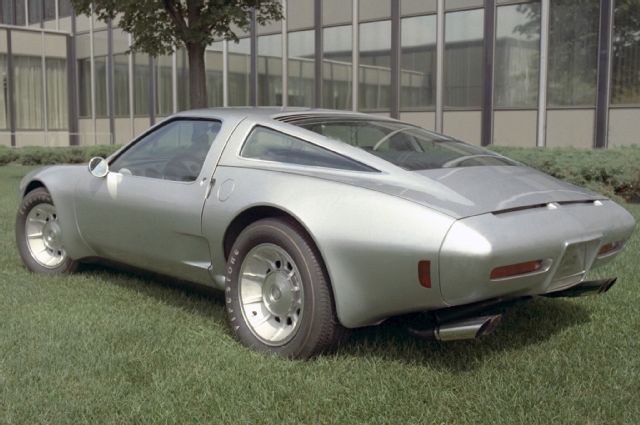

John Z. DeLorean was the General Manager of Chevrolet and always seemed to have his eye fixed on something over the horizon. After the XP-882 chassis improvements were approved, DeLorean authorized Bill Mitchell’s design team to create a new body for the XP-882. Something rounder, with big wheel flares, a sugar scoop rear roof treatment, and NACA ducts on the hood. The final design was nice, but further away from the Corvette “look,” and actually closer to the 2-Rotor Corvette. Oddly, the body was mostly made of steel and weighed 3,500 pounds – about 100 pounds more that a production ’73 Corvette. This would yield no performance improvement at all, so what was the point? Enter Reynolds Metals.

Reynolds Metals (of the aluminum foil fame) had an agreement with GM since 1957 to supply GM the aluminum alloy for Corvair engines, as well as other specialty parts, many of which went into the Corvette: intake manifold, water pump, bellhousing, transmission case, etc. Reynolds also supplied the 390 alloy with 17-percent silicone that was used for the ZL1 block, L88 heads, and Vega engines. On March 13, 1972, DeLorean contracted with Reynolds to build a replica of the XP-895 to see how much weight could be saved if made completely of aluminum. Creative Engineering had already done the fabrication work on the XP-895 and still had the tools and jigs. The 2036-T4 aluminum was a special alloy designed to be spotweldable. Where needed, epoxy adhesive was used with the spotwelding. By June 21, 1972, the completed aluminum XP-895 was delivered to Chevrolet Engineering for final assembly. Because the aluminum chassis was an exact copy of the steel version, everything went together perfectly. The completed steel and aluminum cars were both painted silver and looked totally identical. Except that the Reynolds aluminum car was 38.9 percent lighter, a whopping 450 pounds!

As incredible as that sounds, there were two major problems. First was that handbuilding a one-off car isn’t the same as designing a car to be mass-produced. However, aluminum-alloy forming and joining techniques were worked out, not unlike 20 years before when Chevrolet technicians worked out how to use fiberglass. The second major problem was the killer – cost. No matter how the numbers were crunched or if the car was built domestically or overseas, an aluminum Corvette would cost a LOT more than a steel frame, fiberglass body car. Not much more was disclosed, but essentially, the concept was dead and the XP-895 was put into storage.

On December 31, 1974, Zora Arkus-Duntov officially retired from GM and on January 1, 1975, Dave McLellan became the second Corvette Chief Engineer. In 1979, McLellan was reviewing Chevrolet’s past mid-engine Corvette cars and learned that only the XP-895 was driveable. For most experimental or prototype cars, once the fire of desire goes out, if they aren’t sent to the crusher, all work on the car is stopped. Since concept cars are built to show a concept, they are often not very developed and sometimes don’t work so well, as you will see in our story about the 4-Rotor Corvette. McLellan had the XP-895 rebuilt so that it could be driven. He reported that while the ride was surprisingly soft, it felt heavy and lumbering. The interior was cramped and the “trunk” had enough room for two gym bags (just like the Fiero). I’m sure that from the 1979 perspective, the all-aluminum Corvette concept seemed like a waste. However, what no one dreamed back in the ’70s was that 40-plus years later, the base model, mass-produced seventh-generation Corvette would be riding on a super strong, all-aluminum chassis. And it all began with what looked like a failed prototype project.

Check out the other Experimental Corvette Stories HERE.