Race-prepared, stock 1990 ZR-1 Shatters a 50 Year 24-Hour Speed Record

Dateline: 5.22.17 (This story first appeared in the May 2017 issue of “Vette Vues”) – Racing Corvettes used to have a long history of durability issues. There are many reasons why Corvette racecars had durability issues, but one of the biggest is easy horsepower. It’s always been relatively easy to get a lot of power out of a small-block or big-block Chevrolet engine. If a builder is more oriented towards drag racing, the temptation for an extra 50-horsepower is just too tempting for many builders. That’s fine for drag racing where a car is stressed to the max for a matter a seconds. But in endurance racing, you have to finish to win.

From the perspective of the mid-1980s, the new C4 Corvette was light years ahead of the previous two-generation Corvettes. In the mid-1980s Corvettes were so fierce in SCCA Showroom Stock racing that after two years they were kicked out for being too fast! So, the factory-built Corvette racecars duked it out in their own series, The Corvette Challenge. Breakage with the C4 cars wasn’t much of an issue thanks to the much-improved structure and suspension, plus the cars weren’t powered by massive, torque-monster big-blocks.

In the mid-to-late 1980s there was a ton of very cool work going on in the Corvette design group. Leading the charge was the Corvette Indy program that included the Corvette Indy, the Running Corvette Indy, and the CERV III. Turbocharging was all the rage in the arena of supercars, so a special deal was made with Reeves Callaway and in 1987 RPO B2K, the Callaway Twin Turbo was on the official Corvette order sheet. This was a hold-over car, as Corvette Chief Dave McLellan was working with Lotus on a “Super Vette”, the car that would become the ZR-1 model, powered by the jewel-like DOHC, all-aluminum, 385/405-horsepower LT5 engine.

And this wasn’t just a “big engine” option; it was its own unique model Corvette with an improved suspension and special widebody-works to pull the whole package together. Yes, it was VERY expensive, $27,016, on top of the 1990 base price of $31,979. By the last year for the ZR-1 in 1995, the price had expanded to $31,258 on top of the base price of $36,785 for a grand total of $68,043! The C4 ZR-1 stood as the “most expensive” Corvette until the arrival of the 2008 Z06 ($71,000), followed by the 2009 ZR1 for a whopping $103,300!

In the long and colorful story of performance Corvettes, the C4 ZR-1 is a legendary car. So it was only a matter of time before someone tested the new ZR-1 under racing-type conditions. In the summer of 1989 automotive PR guy, Peter Mills was talking with racer Stu Hayner about speed records and that the according to the team that raced the then-current IMSA GTP 962 Porsche, the Porsche did not have the stamina to break Ab Jenkins 24-hour speed record of 161.180-mph, set back in July 1940 at Bonneville with his massive, 4,800-pound, 750-horsepower, “Mormon Meteor.” Many had tried and failed, including; Ford in 1969, Mercedes-Benz in 1976, and Audi in 1988. Perhaps the new ZR-1 Corvette could pull it off!

It certainly helps to know the right people. Hayner talked with Chevy’s John Heinricy who pitched the idea to Corvette chief engineer Dave McLellan. According to John (as per the story at ZR1NetRegistry.com), “… McLellan was real interested. I don’t remember it going any higher that McLellan. I think we just decided to do it. It was the kinda thing that, if you take it higher, somebody’s just going to say, ‘No.’ Then I talked to Doug Robinson (Development Manager) about a couple of test cars and Jim Minneker (Powertrain Manager) about what powertrain might work.”

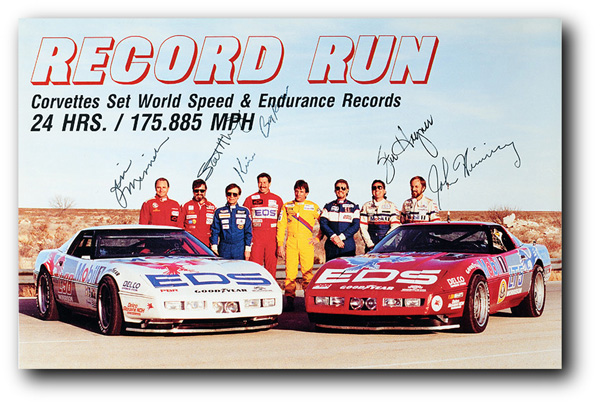

Tommy Morrison was brought on board with his sponsors Mobil Oil. Hayner’s Corvette Challenge sponsor EDS (Electronic Data Systems) and Goodyear wanted in on the project. The other team members included Corvette Challenge driver, Scott Lagasse, Corvette Group Engineers Jim Minneker and Scott Allman; Showroom Stock racers Don Knowles and Kim Baker. The only real change to the speed record plan was to include a racing-prepared stock L98 Corvette.

Another big challenge was “where” to do the speed run. Daytona or Talladega would have had a lot of street cred, but they were too expensive and the high banks would have seriously loaded the suspension of the basically stock ZR-1. Then there was the Nissan track in Arizona, but Nissan was cold to the notion of a “Corvette” going for a speed record at their track. GM had a five-mile Proving Ground, but management had safety concerns, and rightfully so. Finally, the 7.71-mile oval, Bridgestone Tire Proving Ground at Fort Stockton, Texas was chosen by Morrison because of its gentle 7-degree banking.

The track had 1.5-mile long straights and 2.35-mile curves that allowed the car to be driven nearly flat-out. There were three lanes to the track and no guardrails, making driving at high speed a concentration challenge. The track also had no barrier fencing, meaning that it was open to animals, that’s why the cars were equipped with anti-animal whistles, so as to avoid an encounter with a coyote, deer or cow. Seven pairs of men in trucks spaced about a mile apart outside the track used shotgun blasts to keep the critters away!

Where as Ab Jenkins car was an all-out, purpose-built racecar, the ZR-1 and L98 cars were essentially stock with minor racing hardware and full-out safety equipment. The cars pressed into service had already been used by GM-Europe for record runs and were built in late 1989, early 1990, and had been tested at the Fort Stockton facility in November 1989.

Since terminal velocity was the game, a full roll cages and a 45-gallon fuel cells were installed. The suspension was stock but lowered in the front and the rear anti-roll bar was removed to make room for the fuel cell. The ZR-1’s rear used a 3.07:1 gear set and the L98 had 2.72:1 gearing. Engineers calculated that at 190-mph the cornering g-force would be 0.5-g.

Racing at night on an unlit track was a major concern, so the stock headlights, fog lights, and turn signals lights were replaced with racing lights and two aircraft landing lights were mounted where the front license plate was located. Extra oil coolers and differential coolers were added, and the side view mirrors were removed. The Dymag magnesium racing wheels were shod with special-made radial tires from Goodyear that measured 25.5×12.0-17. These were experimental tires that Goodyear reportedly spent $250,000 to make!

The front air dam was enlarged and reinforced and special ultrasonic anti-animal whistles were installed to help keep the critters off the track during the speed run. Inside the interior, the passenger seat was removed and replaced with the EDS telemetry system so that the team would have constant data and contact with the drivers.

John Heinricy gave some interesting inside information about the car’s development. He said, “We did everything we could to mitigate risk. We calculated g-levels we’d be running. Calculated tire loads, We ran tests on the tires. They x-rayed every tire. There was nothing to break as the car wasn’t that stressed. The engine was run hard, but not as hard as we ran them on the dynamometer.”

The FIA rules mandated that a speed record car must carry “non-consumable” spare parts in the event of a breakdown and the driver wasn’t able to get back to the pits for repairs. Consequently, the ZR-1 had to carry an additional 300-pounds of spare parts in two suit cases lashed to the rear roll bar supports of the full roll cage! Drivers were expected to be able to fix the car if something broke.

The LT5 engine for the ZR-1 was taken directly off the Mercury Marine assembly line and was essentially stock. The engine used in the car had a minor balance problem and was never shipped to Bowling Green, so Mercury Marine gave the engine to Morrison. The Morrison team fixed the issue and with headers, open exhaust and controls calibrated for racing fuel, the horsepower was a modest 400-to-410. The engine was built to last, and did so beautifully. Engineers calculated that 190-mph was needed to break the speed record and that 5500-rpm in 5th gear, with the throttle stopped at 70-percent was needed.

Kim Baker built the engine for the L98-powered “regular” Corvette. The only changes Baker made included 11.00:1 compression pistons, high-ratio rockers to increase valve lift, and the production aluminum heads were slightly modified to increase air and fuel flow. The cam was stock and the catalytic converters and mufflers were removed. Both the LT5 and L98 ran full out almost the entire time.

The full team included the drivers, the Morrison Development team, GM, EDS, and STG technicians, engineers from Goodyear, agents of associated sponsors, GM public relations people, and lastly, officials from USAC (United States Auto Club) to officiate FIA record attempts.

Eight drivers took 80-minute driving stints and included: John Heinricy (1989 SCCA Escort Champion and Manager of Corvette Development), Tommy Morrison (owner of Morrison Motorsports), Corvette Group Engineers Scott Allman and Jim Minneker, Showroom Stock racers Don Knowles and Kim Baker, Corvette Challenge racer Scott Lagasse, and Stu Hayner.

It was a cold, windy, overcast, nasty in Texas on the day of the record run. The timed event started at 9:55:12am on March 1, 1990 with John Heinricy at the wheel of the ZR-1 and Tommy Morrison driving the L98. The pace was essentially flat-out! Heinricy said, “Speed was in the low 190s. We didn’t lift in the turns. We entered them foot on the floor and by the time we came out of it, we’d be in the high-170s. It didn’t slow down much in the turns.” Fuel stops only took about 45-seconds to fill the 48-gallon fuel cell. Interestingly, the chassis and tires weren’t really stressed that much by the low cornering loads – something that would have been an issue at one of the high-banked tracks.

By 3:56pm the L98 had set five FIA Category A records, Group II Class 10 records, and the 6 hour speed record at 170.887-mph. Since the car had fulfilled its objective, it was pulled from the event, certified by USAC, then transported to Dallas and air freighted to Switzerland for the Geneva Auto Show – hot off the racetrack!

Meanwhile, the ZR-1 soldiered on through light drizzle and snow flurries, never slowing down. At one point Hayner had a jolting experience when a coyote wandered out on the track. Through the intercom Stu tersely said, “There’s a coyote!” Later he reported, “It came over the outside into my lane, stopped, looked at me for a split second, then went back. That got my attention!” (the coyote’s too!) They also had several encounters with birds on the track. Stu Hayner said, “At 200-mph they vaporize.” Heinricy said, “Usually, you didn’t even see the birds. They just go ‘Bang’ on the windshield. I hit two or three.”

It was a New Moon on March 1st, meaning no moonlight on the unlit track, which proved to be unnerving-to-scary at night, as even with Hella racing lights, the ZR-1 was clearly overdriving its lights. But the ZR-1 and its drivers performed flawlessly and without incident. Considering what they were doing, the location, weather conditions, speed, and length of time – it was an amazing feat! Heinricy and a few of the other engineers did quick calculations on speed/reaction time, plus the reality check of no guard rails, and the possibility of literally flying off the track if “something” should happen. “I was still pretty young, then. I think some of us were thinking: it wouldn’t happen to us. That’s the mentality of most race drivers.”

Patchy fog was another thing that creeped out the drivers. The “good part” was that the patches only lasted a fraction of a second, but a big patch would have been serious trouble. The only nighttime issue was when one of the tire sensor counter-weights came off, causing a nasty vibration that broke off Jim Minneker’s radio microphone wire. A quick pit stop and a tire change fixed the issue.

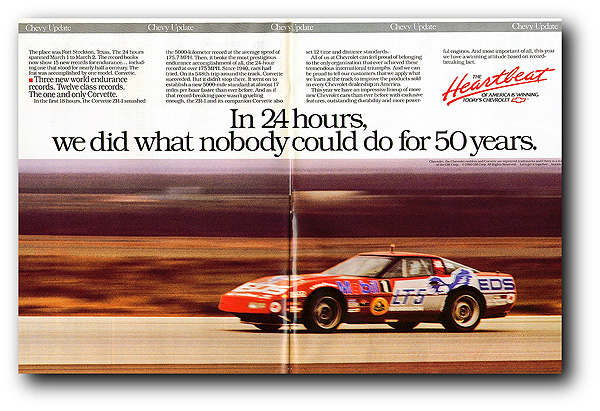

At the 24-hour mark the team was ecstatic with job. They had not only shattered a 50-year speed record, they accomplished their goal with a slightly modified production automobile – Ab Jenkins’ car was a purpose-build racecar with 750-horsepower, the ZR-1 had around 400-410-horsepower. And the sauce for the goose was that Ford, Mercedes-Benz, and Audi couldn’t do what the ZR-1 Corvette team did.

But wait! There’s more!

Since all was well with the ZR-1 and the team was pumped, they decided to go for more – the 5000-mile record was in sight! The ZR-1 thundered on for another four hours when with just eight laps to go, what could have been a major mechanical issue raised its ugly head when Stu Hayner noticed that the engine was seriously overheating. A pit stop showed that the radiator shroud had been rubbing on the water hose, causing a loss of cooling fluid.

With the hose replaced, Hayner and the ZR-1 went back out for the final eight laps, taking it easy on the last lap at “only” 140-mph! The ZR-1 had completed 5000 miles in 28-hours, 46-minutes, and 12.426-seconds. Stu unscrewed the throttle stop and took two hot laps at full-throttle – 15-miles at 190-plus mph, after running for 5000 miles! Can there be any doubt as to the durability of the Lotus-designed, Mercury Marine-built LT5 engine and the ZR-1?

The entire effort was about breaking a long-standing speed, endurance, and distance records. At the end of the experience, the team racked up the following records;

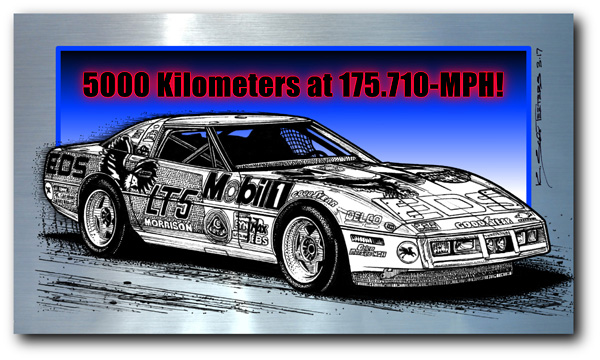

5000 Kilometers at 175.710-mph

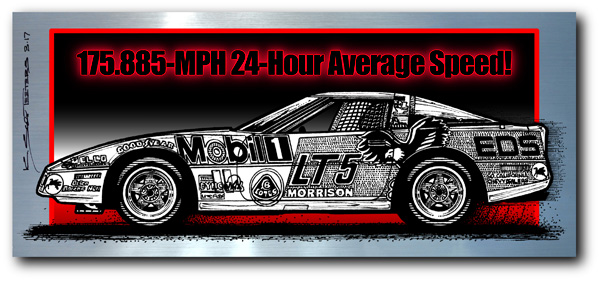

24-Hours at 175.885-mph

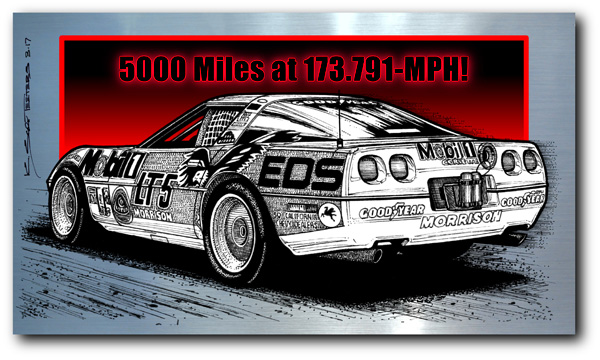

5000 Miles at 173.791-mph

Plus, four FIA International Category Class A-G2-C10

After the event, the entire team signed the underside of the hood. The ZR-1 was cleaned up and went out on a promotional tour as the “World Speed Record ZR-1 Corvette.” Talk about a feather in the cap of Chevrolet and a gold star! Plus the knowing that a production Corvette had done what several other serious competitors could not. There should be no doubt about the capability of the C4 and the ZR-1 – what the team accomplished was mighty impressive.

In the long history of Corvette racing, no other Corvette before or since has accomplished this feat. Yes, the Corvette Racing team has won Le Mans 8 times since 2001 (no small thing!), but these were all, all-out racecars. The Morrison Mobil EDS 1990 ZR-1 Corvette was essentially a stock production car.

A few minor things have bothered me about this story since it was first shared in the automotive press. This is really a minor thing, but the car didn’t have a really cool name. Other Corvettes from the day had cool nick-names: “Conan”, the experimental V-12 Falconer-powered Corvette, “Snake Skinner”, John Heinricy’s super lightweight ZR-1, “Big Doggie” the big-block 454 engineering study Corvette. Perhaps Duntov should have been brought into the effort, then the car could have been called, “Zora Racer-1.” Maybe, perhaps…

The other thing is what the effort was attempted again with the 638-horsepower C6 ZR1. The last ZR1 certainly had the grunt and much improved aerodynamics and ground effects. I suppose it is possible that Chevrolet felt they were getting enough publicity from the Corvette Racing Team; therefore such an effort wasn’t needed. Then again, maybe no one wanted to do such a dangerous stunt, just for speed records.

But John Heinricy put perspective on that question. He told automotive writer Hib Halverson, “People say about the new ZR1, ‘You ought reset that record’ and I think, ‘Do you have any idea what you’re talking about? (laughs). Wow, here’s another person without the foggiest idea what it takes to do that.”

It wasn’t too long ago that late C3 Corvettes were at the bottom of the pecking order of used Vettes. Today it’s the early C4s that can be picked up for the price of a Z07 option on a 2017 Corvette. Even early C4 ZR-1s, 1990 to 1992 can be purchased for between $15,000 and $25,000 depending on mileage and condition (look it up on CarGurus.com), AMAZING! Also, five years before the arrival of the ZR-1, L98 Corvettes were eating everyone’s lunch in SCCA Showroom Stock racing. So, despite the C4’s shortcomings, there was a time when these cars were indeed “King of the Hill.” – Scott