Duntov carried the heart and soul of the Corvette into racing and created an American legend.

(Dateline: 7-3-20 – This story was originally published in the now-defunct Vette magazine, June 2019 issue) Arguably, there had never been a chief engineer of an American car the likes of Zora Arkus-Duntov. When Duntov was hired to work at Chevrolet on May 1, 1953, the 43-year old European-trained engineer brought a background that made him uniquely qualified to become Corvette’s first chief engineer.

As a young man, Duntov was into boxing, motorcycles, fast cars, and pretty girls. After his formal engineering training in Berlin, Germany, Duntov started racing cars and applying his engineering skills to racecar construction. In 1935 Duntov built his first racecar with help from his racing partner Asia Orley; they called the car, “Arkus”. Their goal was to debut the car at the Grand Prix de Picardie in June 1935. But after a series of mishaps, the car caught fire and never raced. From this point forward, all Duntov wanted to do was build racecars.

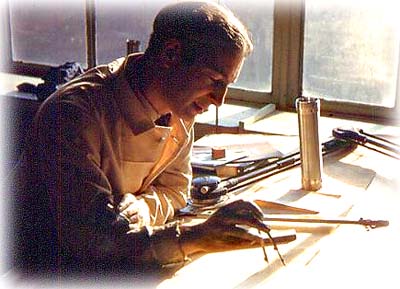

In the 1930s Auto Union and Mercedes built the best racecars in Europe. Duntov wrote a technical paper about a new racing concept for the German Society of Engineers titled “Analysis of Four-Wheel Drive for Racing Cars”. at the 1937 Automobile Salon in Paris, Duntov met Dr. Ferdinand Porsche, the designer of the Mercedes-Benz SS and SSK racers, and French performance-car builder and designer, Ettore Bugatti. Mercedes-Benz cars were complex engineering marvels, but Duntov appreciated Bugatti’s elegant simplicity, raw speed, and the success of his cars with privateers. “Simplicity and privateers” are two hints of things Duntov would later do with Corvettes.

After marrying Elfi Wolff in 1939, war broke out in Europe, and Duntov and his brother Yura had a brief stint in the French air force. France fell quickly and Duntov and his family made their way to New York. The brothers setup the Ardun Mechanical Corporation and worked through the war years as parts suppliers for the U.S. military. After the war Duntov and Yura turned their attention back to racecars and started producing their Ardun Hemi Head Conversion kits for flathead Fords.

Post-war years were difficult and by the early ‘50s Duntov was looking for an engineering job with a major Detroit car company. His goal was to find a company that would let him build racecars. When Duntov saw the first Corvette at the 1953 Motorama, he immediately pursued GM, specifically to work on the new Corvette. Chevrolet general manager Ed Cole hired Duntov and assigned him to work under GM suspension master, Maurice Olley; the clash was immediate. Olley was reserved and a numbers-cruncher; Duntov was outgoing and designed by intuition. Six weeks after being hired, Duntov requested time-off to race a Cadillac-powered Allard JR at The 24 Hours of Le Mans. Olley refused, but Cole got him off the hook to race at Le Mans, but without pay. Duntov was so irritated that he almost didn’t come back from France. After his return, Duntov reassigned and started testing special parts to improve the Corvette’s suspension and general performance.

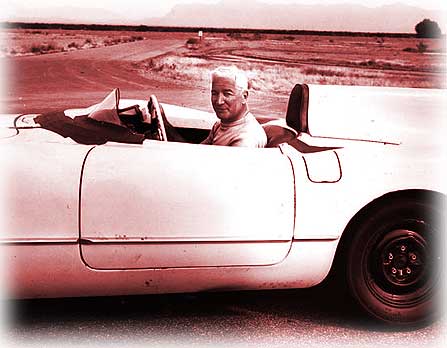

When the 265 small-block became available in 1955, Duntov took a modified ’54 Corvette with the new engine and some aero mods to the GM Phoenix Arizona test track where he was clocked at 162-mph. The mule Corvette was later rebodied as a ’56 Corvette and was part of a team of three Corvettes that were taken to the 1956 Speed Weeks event at Daytona Beach where Corvettes set speed records. Then in March at the 1956 12 Hours of Sebring race, Corvette scored its first major class win. Duntov and three-time Indy 500 winner and engineer Mauri Rose were then tasked by Ed Cole to design, develop, and make available, special Chevrolet-engineered racing parts. When the Rochester Fuel Injection option was released in 1957, RPO 684 Heavy-Duty Racing Suspension was there for privateers that wanted to race their Corvette.

The Bugatti pattern was laid down; make simple, fast cars, and let the privateers do the racing. Duntov also built a few purpose-built Corvette racecars. The 1957 Corvette SS was a good first step but the timing was bad because of the 1957 AMA Racing Ban. The Grand Sport was similar to the RPO Racer Kit program, only a complete, basic racing Corvette was to be sold to privateers. Again, the AMA Racing Ban killed the project. If Duntov hadn’t pushed racing, the Corvette would have morphed into a Thunderbird-like four-seater and been killed by the early ‘60s.

Duntov laid out three design concepts that took decades to implement. The first was his proposal for the 1957 Q-Corvette. This design called for the following: an all-aluminum, fuel-injected small-block engine, four-wheel independent suspension, four-wheel disc brakes, and a transaxle. This design concept arrived in 1997 as the C5.

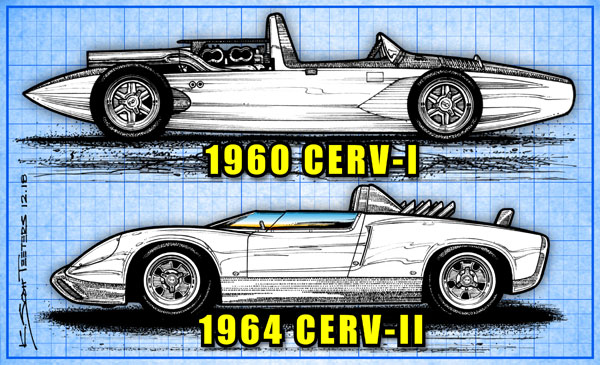

The second design concept was the mid-engine layout. Duntov’s first mid-engine concept was the 1960 CERV-I. The design parameters were those of an Indy 500 racecar, but with a larger engine. Duntov’s second mid-engine car was the 1964 CERV-II. The third concept in the CERV-II was its unique four-wheel-drive system. Using transaxle parts from the Pontiac Tempest, the system “worked” but would not have lasted as a racecar.

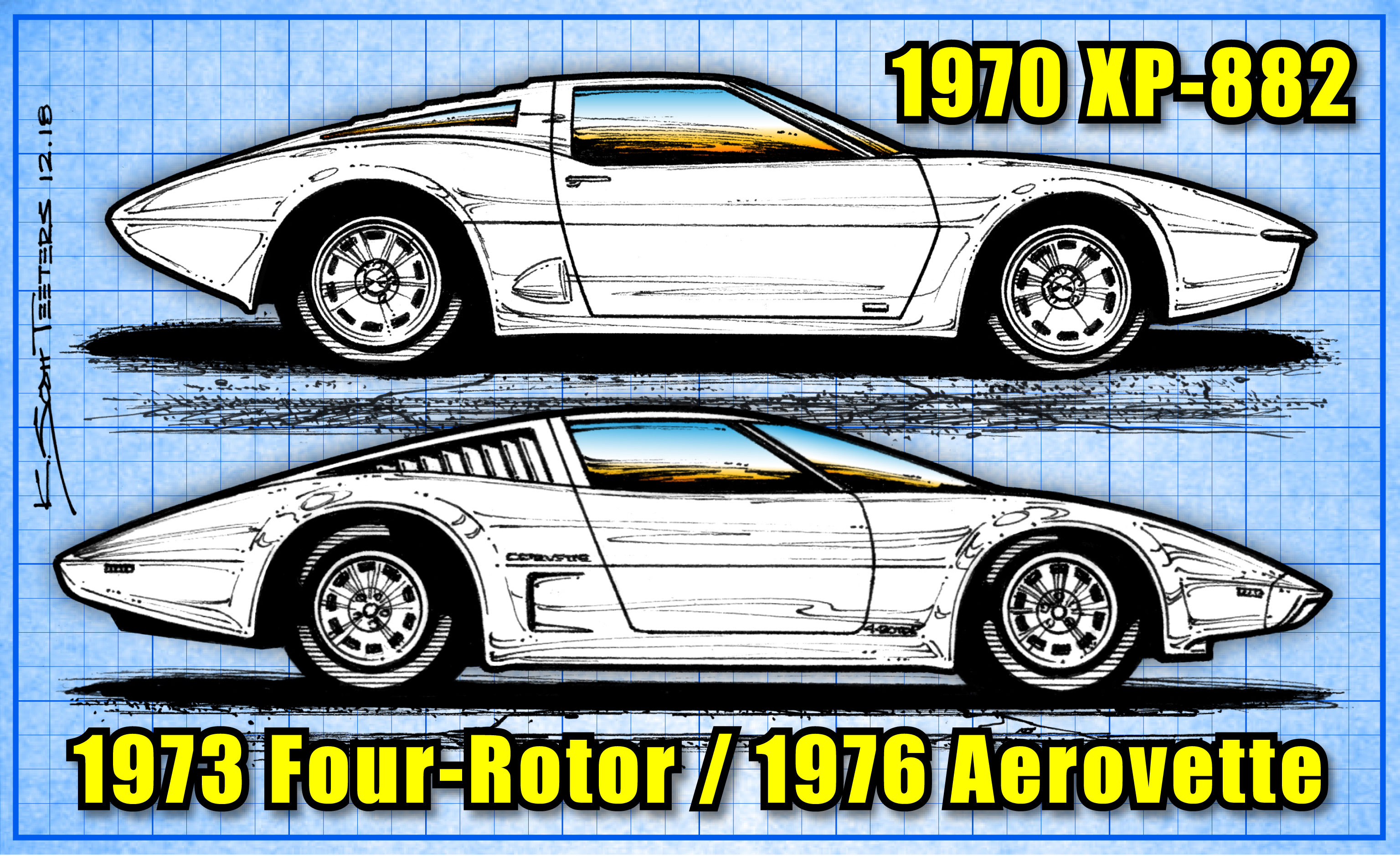

Through the ‘60s several other mid-engine “Corvette” cars were built, but not by Duntov. Engineer Frank Winchell’s 1968 Astro-II Corvette was a beautiful attempt, but like all mid-engine Corvette proposals, it went nowhere. In 1970 Duntov showed his XP-882 with a transverse-mounted 454 engine. After the car was shown at the 1970 New York Auto Show, it went into hiding for some reason. Later, the chassis was used to build the Four-Rotor mid-engine Corvette that was later retrofitted with a small-block engine and rebranded “Astrovette” in 1976, after Duntov retired.

Just after the debut of the C7, the Corvette community started buzzing about the mid-engine C8. For a time the C8 was an unconfirmed rumor until Chevrolet announced that, yes, a mid-engine Corvette was in the works. In 2018 camouflaged mule cars started being seen on public roads. In July 2018 a camouflaged C8.R was seen being tested. Towards the end of 2018 speculation was that the C8 would debut at the 2019 Detroit Auto Show. Then in December 2018, Chevrolet announced that the C8 would be delayed “at least six months” due to “serious electrical problems.”

An insider friend has been telling me for over a year that they were having serious problems getting the car right, but he wasn’t specific. Then another hint was dropped; the problem is with the car’s 48-volt electrical system. Why would the C8 have a 48-volt system? Answer; because it will have auxiliary electrical front-wheel drive. Suspension and traction is everything, so AWD is inevitable.

While Duntov didn’t “predict” the Corvette’s future, he certainly set the course. His insistence that Corvette be tied to racing, kept the car from becoming Chevy’s Thunderbird. The features of the 1957 Q-Corvette are the very design foundation of the C5, C6, and C7 Corvette. The CERV I, CERV II, and the XP-882 (minus the transverse engine) will live in the mid-engine C8. And it is likely that the CERV II’s all-wheel-drive concept will live in the C8, only as an electrical, and not a mechanical system. Without one man’s obsession with building racecars, there’d be no Corvette legend. – Scott

Be sure to check out the Duntov installment of my “Founding Fathers, Pt. 4 Zora Arkus-Duntov”, HERE.

Also, catch all 5 parts of my Corvette Chiefs Series

Corvette Chiefs, Pt. 1 – Zora Arkus-Duntov

Corvette Chiefs, Pt.2 – Dave McLellan

Corvette Chiefs, Pt. 3 – Dave Hill

Corvette Chiefs, Pt. 4 – Tom Wallace

Corvette Chiefs, Pt. 5 – Tadge Juechter