Dave McLellan, Heir to Duntov’s Engineering Throne

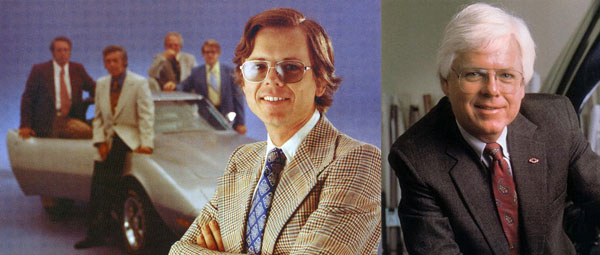

(Dateline: 7-3-20 – This story was originally published in the now-defunct Vette magazine, July 2019 issue. Story, Illustrations & Graphics by K. Scott Teeters) – When Dave McLellan took over as Corvette’s new chief engineer on January 1, 1975, it was a whole new world. The prevailing trends went from performance cars to safer cars with reduced emissions. Not even Duntov could have made a difference in the ‘70s. But as performance went down, Corvette sales went way up! The sales department was happy, but the Corvette was really getting old. Dave McLellan was an unknown to the Corvette community and many wondered what he would bring to the brand. It turned out; he brought a lot!

McLellan was a car guy. He rebuilt his family’s Frazer and entered the Fisher Body Craftsmen’s Guild Model Contest. Upon graduation from Wayne State University in Detroit with a degree in mechanical engineering, GM hired Hill on July 1, 1959. Thought the ‘60s Hill worked at the Milford Proving Ground on noise and acoustics issues with GM tank treads, Buick brakes, and tuned resonators for mufflers. Hill was also going to night school to get his Master’s Degree in engineering mechanics. In 1967 Hill was part of the group that planned and operated the 67-acre Black Lake where ride, handling, and crashworthiness tests are performed.

Chevrolet engineering brought in Hill to work on the 1970-1/2 Camaro and Z28. Hill wanted to move into management so he took a yearlong sabbatical and attended MIT Alfred. P. Sloan School of Management. The school emphasizes innovation in practice and research. In July 1974 Hill was Zora Arkus-Duntov’s part-time assistant, training for taking over the position in 1975.

While Hill didn’t have Duntov’s racing experience, he owned several Porsches and understood racing sports cars. As Duntov was leaving, he told Hill, “Dave, you must do mid-engine Corvette.” Little did they know that it would finally happen forty-five years later.

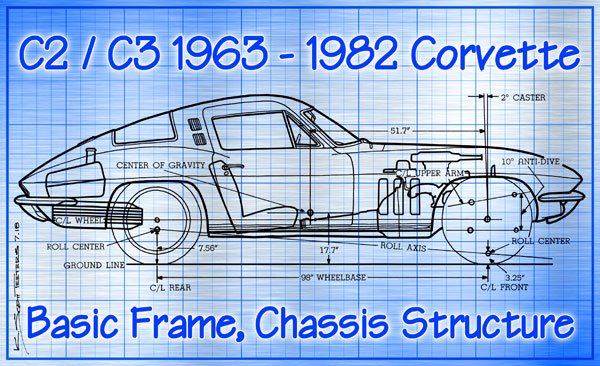

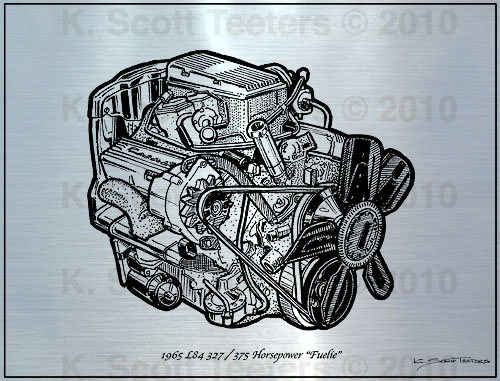

When Duntov took control of Corvette engineering in 1956, he had to boost sales and make the Corvette a performance car and a capable racecar. When Hill took control, Corvettes were never selling better, but the platform design was nearly fifteen-years-old. Hill had to keep the car fresh, hit the new requirements, and maintain performance; all with a limited budget.

Management figured that the Corvette had a captive audience, so they didn’t have to spend money to change anything. Fortunately, that lame notion was overruled. The 1978 glass fastback and the 1980 front and rear bumper covers were excellent updates. Another major issue was quality control. The St. Louis assembly plant made three other cars and often workers were unfamiliar with the specialties of the Corvette. This issue didn’t get fixed until the plant was moved to the Corvette-only Bowling Green facility.

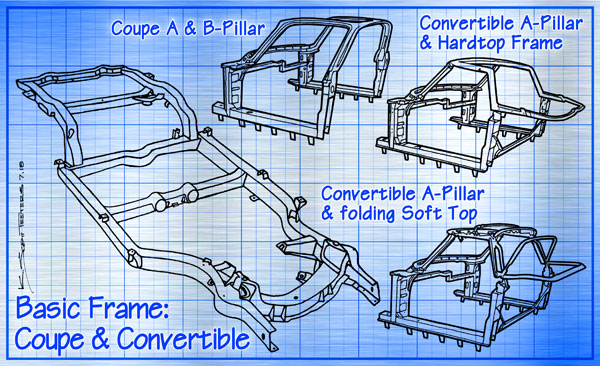

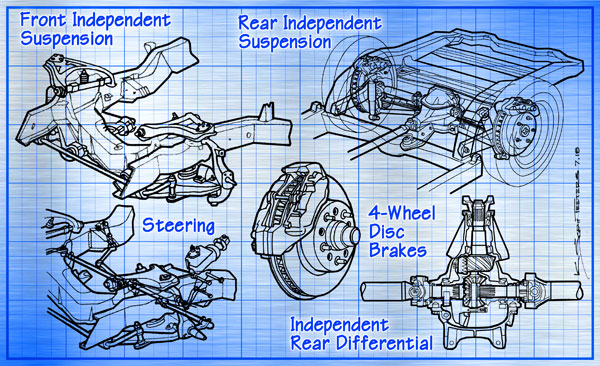

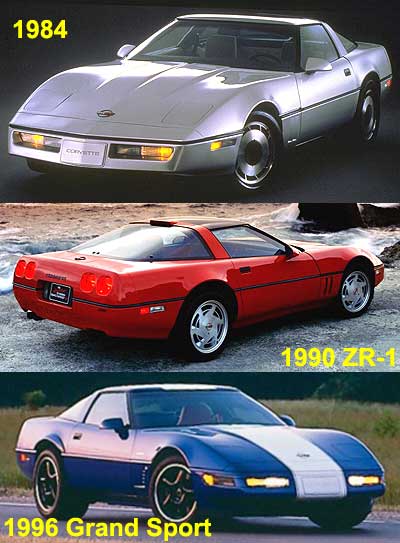

McLellan knew that the C3 needed to be replaced, as the chassis was designed around 1960! For a brief period, it looked like the mid-engine Aerovette would become the C4, but Chevrolet decided to abandon all mid-engine programs. The all-new C4 began to take shape in Jerry Palmer’s Chevrolet Studio Three in 1978. When the C4 debuted in December 1982, it received rave reviews, despite the fact that suspension engineers later admitted that they over-did-it with the stiff suspension. By 1985 the suspension was softened and the 150-mph Corvette won Car and Driver’s “Fastest Car in America” award and began the total domination of Corvettes in the SCCA Escort Showroom Stock racing series from 1985-to-1987. Porsche bought a Corvette to take apart to find why the car was unbeatable. By the end of 1987, SCCA kicked out all of the Corvettes for being too fast! McLellan followed up with the Corvette Challenge factory-build racecars.

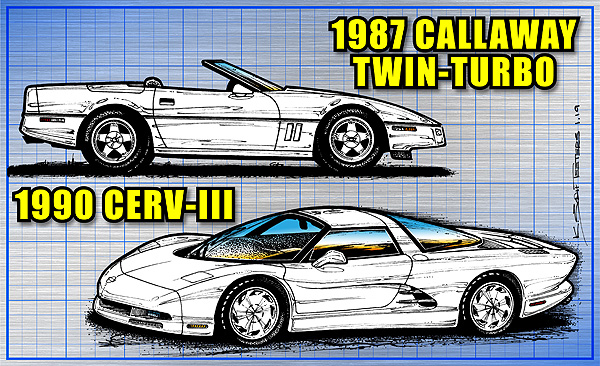

McLellan’s personal style was more suited to the intricacies of modern electronic computer-controlled performance cars than Duntov’s. Where Duntov’s enthusiasm was effervescent, McLellan was laid-back, approachable, but not shy with the automotive press. After the successful rollout of the C4, McLellan took on four very serious performance projects for the Corvette; The Callaway Twin Turbo option, the ZR-1 performance model, the LT-5 Lotus/Mercury Marine performance engine, and the mid-engine CERV-III. Let’s look at all four projects.

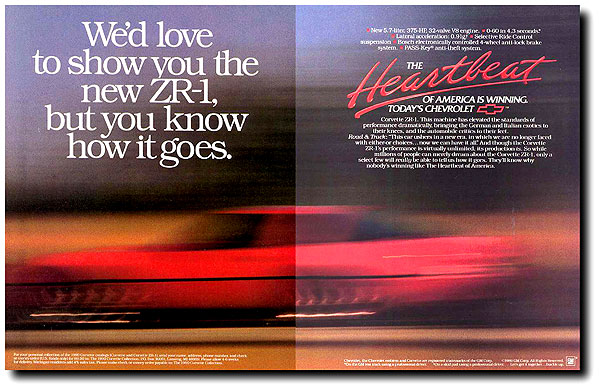

“Supercars” were the rage and by 1985 Porsche had their 959 and Ferrari was about to unleash their F40. To have something to offer while McLellan was starting his ZR-1 project, a deal was made with Reeves Callaway to build brand-new Corvettes with a Callaway Twin Turbo package. The cars had 345-horsepower (stock Corvettes had 240) and from 1987-to-1991 RPO B2K was the only non-installed official RPO Corvette option ever offered.

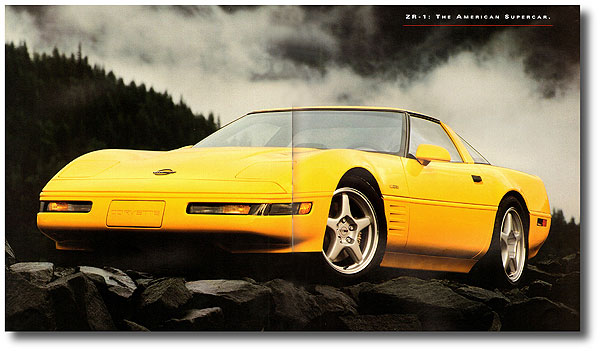

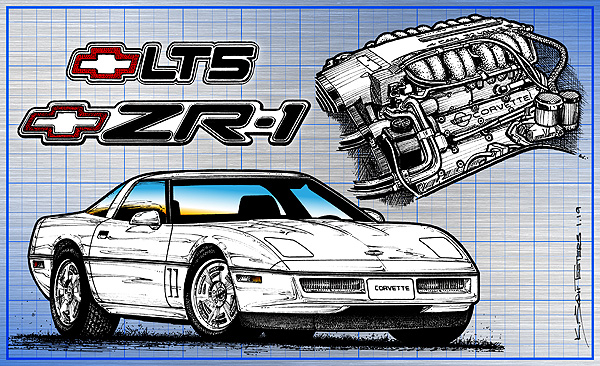

The ZR-1 super-Vette had two components. The first was its Lotus-engineered, all-aluminum, double-overhead-cam engine built by Mercury Marine. McLellan’s engineers set down the size parameters and horsepower objective; Lotus did the rest. McLellan turned to the best manufacturer of all-aluminum, performance marine engines in the country, Mercury marine. The end result was the beautiful jewel-like LT-5, an engine that is still respected today. The second component was the widening of the ZR-1’s body to cover the enormous P315/35ZR17 rear tires and beef up the car’s drivetrain and suspension.

The 1990 CERV-III Corvette was McLellan’s vision of Duntov’s mid-engine Corvette, with electronic steroids. The car had a carbon fiber Lotus-style backbone chassis, four-wheel steering, active suspension, a transverse, 650-horsepower twin-turbocharged LT-5 ZR-1 engine and a dry-sump oil system, and a four-speed transaxle. This was the final design that started out as the Indy Corvette in 1986 and had a top speed of 225-mph. And lastly, the CERV-III was designed to be manufactured.

When McLellan was part of the 1992 “Decision Makers” three-man internal Chevrolet design group, gathered to evaluate the direction of the C5, McLellan chose the CERV-III concept over the front-engine “Momentum Architecture” and the stiffer/lighter restyled C4. But the CERV-III was deemed too expensive for the market. The “Momentum Architecture” with its backbone structure, a transaxle, and an all-aluminum engine with design elements from the LT-5, lives on today in the C7.

McLellan oversaw the three-year, 1990-to-1992 mid-cycle refresh. The process started in 1990 with an all-new dash; 1991 saw new front and rear bumper covers; and in 1992 the 245-horsepower L98 was replaced with the 300-horsepower LT1.

In 1990 McLellan won the Society of Automotive Engineers’ Edward N. Cole Award for Automotive Engineering Innovation. In 1991 GM was offering early retirement packages, allowing 53-year old employees to receive the same benefits as those retiring at 62. McLellan took the offer and stayed on as a consultant while GM looked for a suitable replacement. McLellan was fortunate enough to be in his consulting position on July 2, 1992, when he was on hand to see the one-millionth Corvette roll off the Bowling Green assembly line. What a thrill for a car that McLellan had given so much to and a car that was so often on the line for its survival.

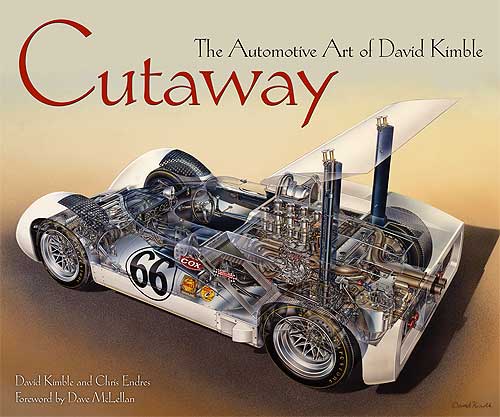

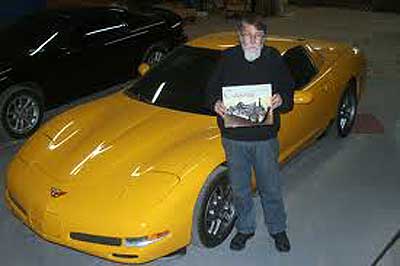

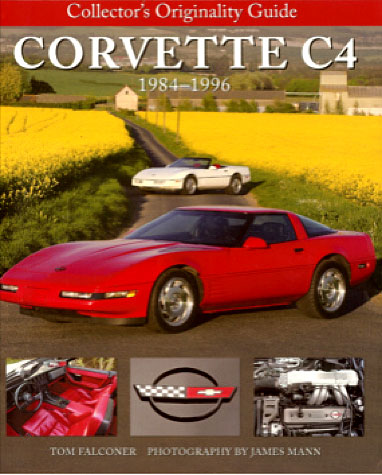

Finally, on November 18, 1992, the new chief of Corvette engineering was Dave Hill. Since then, McLellan has been a much sought after automotive consultant, he wrote and illustrated “Corvette From the Inside” and he’s a frequent and revered guest of honor at all of the top Corvette events. In 1999 McLellan was inducted into the National Corvette Museum’s Hall of Fame. McLellan goes down in the Corvette history books as the second of the five great Corvette chief engineers. – Scott

PS – Be sure to catch all 5 parts of my Corvette Chiefs Series

Corvette Chiefs, Pt. 1 – Zora Arkus-Duntov

Corvette Chiefs, Pt.2 – Dave McLellan

Corvette Chiefs, Pt. 3 – Dave Hill

Corvette Chiefs, Pt. 4 – Tom Wallace

Corvette Chiefs, Pt. 5 – Tadge Juechter